You may well ask what the hell Hemingway has to do with Tiki culture, that mid-century fad for flaming rum drinks, pupu platters, and limbo-lines – a fad that is currently making a revival in metropolitan centers across the United States. The connection isn’t obvious, at least until you look for it, but even a quick google search makes clear that there is some kind of kismetic relationship between Hemingway and the fantasy and booze driven need to escape from modern culture that marked Tiki’s initial spread and its current popularity. Allow me to offer some examples:

- In celebration of Hemingway’s birthday, the Lei Low, a tiki-bar in Houston, has been known to transform itself into a Havana-themed bar.

- · There is Hemingway’s Lounge on Hollywood Boulevard, an African themed tiki bar – and which is in no way affiliated with the five Hemingway’s Bar’s in Bosnia (Zagreb’s being the most popular).

- · There are literally hundreds of tiki bars, blogs, and even podcasts that feature Hemingway-themed drinks, from the Papa Doble Daiquiri, to the “Hemingway Hated Hawaii” cocktail, to Lucky Joe’s “Kitten Mittens” named after Hemingway’s 6-toed cats. The Tiki Lounge in Melbourne Australia even has an entire section of Hemingway drinks.

- · And of course one can sip these drinks out of the Papa Tiki cup, from Cheeky Tiki in the UK, based upon the famous Karsh photograph, and known variously as the “papa mug” and “To have and have not—the mug,” which can be yours for £15 plus shipping.

- And though they are not about tiki culture per se, but rather cocktail culture in general, there are the two Hemingway cocktail books: Hemingway and Bailey's Cocktail Guide to Great American Writers (2006) and To Have and Have Another: A Hemingway Cocktail Companion (2012).

These examples may be surprising, humorous, or disturbing depending upon how knowledgeable or protective one is of Hemingway’s legacy. The fact that Hemingway’s brand has been so absorbed into not just popular culture, but more specifically given these examples, kitsch and drinking culture, is telling, but really should come as no surprise. Since the 1950s, Hemingway’s public persona had little to do with the man himself, his pain, struggles, or humanity, let alone his literature. In All Man!, I wrote about how Hemingway’s image was adopted by a generation of men’s magazines in the 1950s, skewed to hyper-masculine, misogynistic, and debauched proportions, despite the fact that Hemingway’s work, especially late in life, was situated not at the extremities of gender and identity, but where gender and identity break down, cannot negotiate modern life along traditional lines.

Yet Hemingway’s name is still synonymous with the traits and actions of hyper-masculinity, as most recently parodied in The Heming Way: How to Unleash the Booze-Inhaling, Animal-Slaughtering, War-Glorifying, Hairy-Chested Retro-Sexual Legend Within, Just Like Papa! Unfortunately, the irony upon which such a parody is based is lost on some people (as I experienced at a book signing where a woman told me that what America needed was more men like Hemingway to counteract all the modern feminized Politically Correct metrosexuals). All too often, Hemingway has become a cartoonish fiction in popular culture, all beard, bluster, and bombast -- most famously embodied in the silly Hemingway look-alike contests of Key-West.

Macho too mucho in Key West

In this blog post, I’d like to look beyond this popular misrepresentation of Hemingway, and at the actual foundations of the relationship between Hemingway and Tiki culture that goes beyond the clichéd myths of a super-human tolerance for alcohol, and to much deeper tenets of both Hemingway’s work and the Modernist movement. Therefore, this post isn’t as concerned with celebrating either that larger-than-life Hemingway of the 1950s, nor the wonderful tackiness of Tiki culture (though there will be some of that) but to examine how the modernist primitivism of the 1920s eventually became the popular Tiki-primitivism of the 50s and 60s, and accordingly, how this illuminates a “thematic genealogy” of Hemingway’s own work from his early nature writing to late popular works like The Old Man and the Sea.

Indulge me while I wax a little professorish: By “thematic genealogy,” I mean that Tiki culture was a popular fascination with the primitive which relied upon certain themes – naturalism, primitivism, and visuality –that had fascinated Hemingway in the 1920s and surfaced in his writing on hunting, travel, and bullfighting. Understood in this genealogy is the idea that the mid-century marked a time when modernism, embodied in Hemingway himself, became a popular way for the American public to navigate the traumas of modern life, specifically the traumas of technology (such as the cold war, nuclear threat), commercialism (commodification of society and gender, corporatism of American life), and social conformity (suburbanization, McCarthyism).

The Modern Primitive

I've used that term “Primitivism” a few times and it probably warrants a little definition. Primitivism is the fascination and involvement with earlier or indigenous cultures as a means to escape, critique, or reinvigorate one’s own “modern” culture – which was a central tenet of both literary and artistic modernism. Yet the idea and very term Primitivism is problematic, semantically bound up with value judgments and innate prejudices (i.e. the idea of a primitive culture can only exist if it is based upon the inherent superiority and ideologies of the “modern” non-savage culture of the west). The idea of judging another culture as “primitive” necessitates an imperialist mindset that performs an imaginative “colonization” of other cultures towards one’s own ends. Western artists used a reductive and often dehumanized idea of other cultures in order to comment upon or step outside of their own culture, rather than to understand and appreciate the richness (or even the subjugated plight) of the indigenous culture. There are plenty of examples of such dehumanizing attitudes in Western literature, even in works that attempt to critique Imperialism, such as Conrad’s Heart of Darkness which looks to Africa as a tonic to modern civilization’s hypocrisy. For the narrator Marlowe, the natives “had faces like grotesque masks—these chaps; but they had bone, muscle, a wild vitality, an intense energy of movement, that was as natural and true as the surf along their coast. They wanted no excuse for being there,” in comparison to the Europeans who are mostly there to pillage the land of Ivory and natural resources and do so under the façade of cultural betterment, yet the characterizations ofthe natives are stereotyped and romanticized as savage. These characterizations become quite clear as the text became canonized, hence decontextualized, separated from the travesties of the Belgium Congo – these savage (and licentious) characterizations are nowhere more evident than in popular, later editions such as this paperback from the 1950s.

Ultimately, Modernist Primitivism has nominally been attached to western fascinations and fantasies of otherness, but was ultimately implemented as a means to understand not the other but ourselves and our own modern culture via a place of otherness or alienation. In Heart of Darkness, Kurtz’ African bride was used symbolically to indicate both Kurtz’s sin of (literally) going native (as pictured here) and as counterpoint to the benevolent purity of Kurtz’ betrothed back in London. And this symbolization hinged upon the African bride’s highly eroticized and animalized characterization, which is common to most representations of the exotic other in Western Literature, whether African, African American, or American Indian. The type of primitivism in Conrad’s foundational modernist work only identifies a dynamic that would become more and more central to modernist art and literature in the first decades of the 20th century, and can be found in Hemingway’s licentious representation of the Obijway girl Prudie Mitchell, who breaks Nick’s heart in the short story “Ten Indians,” because she “Threshes around” in the woods with Frank Washburn. He would later conflate Prudy, now named Trudy, with sexuality in “Fathers and Sons,” a story of Nick’s adult years. When his son asks what it was like to be with Indians, Nick reminisces about sex with Trudy – and you’ll have to excuse my quoting of one of those overdrawn and slightly uncomfortable metaphoric Hemingway descriptions of sex: “Could you say she did first what no one has ever done better and mention plump brown legs, flat belly, hard little breasts, well holding arms, quick searching tongue, the flat eyes, the good taste of mouth, then uncomfortably, tightly, sweetly, moistly, lovely, tightly achingly, fully, finally, unendingly, never endingly, never to endingly, suddenly ended, the great bird flown like an owl in the twilight, only it was daylight in the woods and the hemlock needles stuck against your belly.” The End. Hah. Notice though how Trudy metaphorically links Nick closer to nature, linked to both the woods and animalism via the post-coital “great bird.” Hemingway distrusted metaphors and we should perhaps distrust this one in that Nick’s description falls into almost stereotypical Indian-like metaphor: (We can almost hear “huh! Great Bird Fly at Twilight.”) The Indian’s naturalism and licentiousness is further confirmed in that Trudy’s brother watches the two make love and, to a certain extent, urges Nick on (or perhaps pimps his sister out) by asking “you want Trudy again?” This identification of the ethnic other as overtly sexual remains with Hemingway throughout his career, and can be seen elsewhere in Green Hills of Africa or, metaphorically, in the fetishization with tanning in Garden of Eden.

Hence we see continuity between the kind of eroticized and naturalized primitivism found in Heart of Darkness and Hemingway’s work, and which, to a certain extent stemmed from the turn-of-the-century cultural milieu. Heart of Darkness, published the same year as Hemingway’s birth, was after all contemporary to the “back to nature” and “physical culture” movements in America – movements central to Hemingway’s own boyhood and upbringing. Encroaching industrialism threatened Hemingway’s boyhood home of Oak Park, outside of Chicago, as did the lumber industry his family’s Michigan retreat. The rise of national parks, the popularity of nature writing by authors such as Roosevelt and Ernest Thompson Seton, and movements like the boy scouts all point to the growing “need to escape” from the quickly modernizing world. Perhaps the most popular American example of this is 1912’s Tarzan of the Apes by another Oak Park author, Edgar Rice Burroughs, which introduced the world to an English Lord and his mate who heroically prefer the wilds of Africa over the lies and hypocrisy of the modern world. This “back to nature” attitude is manifest in Hemingway’s early short stories, most famously “Big Two Hearted River,” where Nick Adams escapes the traumatizing effects of industrialized warfare by losing himself in the wilderness. The return to nature, and its potential to heal the modern condition, was a theme that fascinated Hemingway throughout his life and work. He returned to it again late in life in the Nick Adams novel he started and abandoned, a part of which was published as “The Last Good Country,” wherein a young Nick and his sister live in the wild in order to escape federal Game Wardens (who are indeed civil regulators of nature). Adams, after all, references Adam, the first man, cast into the wilderness, separated from Eden.

I’ll return to these themes later as found in his writing of the 1950s, but suffice it to say that during Hemingway’s formative years naturalist themes were common in popular fiction. (Indeed, Hemingway submitted to pulp magazines, including Blue Book, which often published Burroughs. We even have some of the rejection slips from these magazines). Regardless, when young Hemingway landed in Paris in 1922, and was quickly introduced to modernist art and literature at the hands of Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound, Modernist Primitivism would have not only appealed to him but been familiar. The work of artists like Picasso, Juan Gris, and Matisse were heavily influenced by the simplistic lines of African masks and totems. The most famous example of modernist primitivism is of course Picasso’s Les Mademoiselles de Avignon, and indeed one of the direct precursors of this painting, or at least of this stage of Picasso’s development, was his portrait of Gertrude Stein. Both stein and Picasso had been introduced to African art in 1906 by Matisse, and both had been enthralled with it – enough so that Stein purchased a series of African artifacts for Picasso twelve years later, and we can see an African statue displayed prominently on Stein’s writing desk in this frontis for The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.

The lure of primitive art served many purposes for the avant-garde artists of the early 20th century:

1) Primitivism marked a break with the traditions of academically defined art, as well as the general feeling of otherness, alienation, and dislocation from standard society that marked the “modern condition.” This was especially true for German Brucke painters who displayed their work alongside oceanic objects, as well as for Picasso, who saw the primitive as oppositional to western traditions and subjects of art. And French surrealists Paul Eluard and E.L.T. Mesens literally used primitive art to illustrate their alienation by posing and attending events wearing African masks..

Exhibition of Brucke works

2) Generally, it marked a purity of art, a simplicity that brought the form back to its irreducible building blocks yet still allowed for stylistic abstraction. Influenced by such primitivism, Cezanne stated that all nature can be represented by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone. Post-impressionists relied upon the repetition of such basic forms to duplicate the effect of depth and abstraction achieved in Primitive art (evident below).

Notice the repetitions of forms, specifically rectangles and triangles, in the composition of these paintings

3) The primitive indicated a freedom from western mores and social constrictions, as well as indicated heightened sexuality – which becomes obvious when we realize that Les Mademoiselles de Avignon originally depicted prostitutes, bringing us back to how ethnicity often signified open or aggressive sexuality.

4) For others, such as Gauguin, it marked a return to what was conceived as a simpler time and culture as embodied in the simplicity of shape and line in indigenous (whether African or Polynesian) sculpture, as well as a perceived nievate and childlike simplicity of foreign places. This was really very central to the initial acceptance of Post-Impressionism. For example, the poster for Roger Fry’s 1910 exhibit on “Manet and the Post Impressionists,” an exhibit so important to the British avant-garde that Virginia Woolf stated that because of it “human character changed,” featured a painting by Gauguin of a woman with a Tahitian statue, highlighting the two main dynamics of the movement: Modern and Primitive.

5) And finally, this reliance upon pre-Judeo-Christian, non-western, or archetypal forms reinvigorated contemporary art that was seen as “worn thin by ages of careless usage.” This explains why great modernist works of literature looked to the past for their narrative structures: Joyce’s Ulysses used Homer’s The Odyssey; Eliot’s Wasteland, Pre-Christian Fertility Cults and The grail Myth; and W.B. Yeats used Irish Mythology.

Hemingway and the Primitive

In a late interview for The Paris Review, Hemingway listed Gauguin as one of his influential literary forebears and he often cited Cezanne as a central influence. It is commonplace to discuss Post-Impressionism or Cubism and Hemingway, especially in regard to how his seemingly simplistic style evokes impressions of larger themes, but this short history also makes clear that we can embed his work in a larger modernist fascination with primitive art as well. Indeed, Hemingway often described trying to find linguistic equivalents to a purity of form, how the simplicity of description, or how taking emotionally charged events down to their basic elements produced a much more powerful effect, another dimension of depth. This is exactly what primitive art inspired in cubism – simplistic forms taken down to their basic elements, and the tension between simplicity and depth is forced upon the reader and the viewer not only through repetition but via contrast, as when cubist art is positioned against Oceanic sculpture in the Brucke exhibition or, better yet, in Man Ray’s portrait of Kiki below which forces us to consider his model in terms of abstraction due to the forced dialogue, both similarities and differences, between them (black/white, flesh/wood, horizontal/vertical, modern/primitive, etc). Therefore, stories such as “the Snows of Kilimanjaro” and “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” force the same counterpoint between the modern subject and the primitive: we are forced to reconsider the importance of our own values and lives through the slow death brought about by the Primitive conditions of Kilimanjaro, and we’re forced to see the modern politics of gender Macomber through the back drop of the African Safari.

Man Ray's portrait of Kiki

The modern primitive forces the re-evaluation of the modern through a juxtaposition between or alienation of the modern perspective and the “shocking” or “brutal” primitive – though they do not bring about (nor are they interested in bringing about) a fuller understanding of the primitive object. In other words we can only view these from the perspective necessitated by the forms of modern literature, the short story or the art gallery rather than the oral tale or the ritual; we cannot return to a pre-modern point of view since we are already formed by the modern.

This is getting a bit heady, a bit too lit-crit, so let it suffice to say that Hemingway often uses both primitive settings and simplicity of form in order to better understand the modern situation, his characters, and narrative, much as Picasso relied upon African masks as cubist elements to comment upon our own fractured identities or the limits of the traditional (i.e. sanctioned) artistic styles. In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway describes his fascination with the bullfight by saying that “I was trying to learn to write, commencing with the simplest things, and one of the simplest things of all is and the most fundamental is violent death.” He was trying to take both the sentence and life down to their basic elements (declarative sentence structure, life and death): like Nick in “the Big Two Hearted River” and like the action in so many of his works, Hemingway wanted to “go back to basics” – which also describes other modernists’ fascination and use of Primitive art.

With more space, I would discuss how Hemingway’s uses the primitive, namely in his African and Bullfight scenarios, in order to explore narrative, representations of reality, and issues of self-identity, how both Green Hills of Africa and Death in the Afternoon become grand metaphors for the spoils of the writer’s marketplace and the nature of writing and reception. It is enough to say that through the 1930s, Hemingway’s writing – both fiction and non-fiction -- positioned him as an expert on two key contact zones where modern culture interacts with the primitive, one literal – the safari – and one symbolic – the bullfight. In popular culture, Hemingway became the great white hunter and the great aficionado, the translator of ritualized and primitive art for the common man. Death in the Afternoon, Green Hills of Africa, and Hemingway’s essays in Esquire – what John Raeburn calls Hemingway’s “public personality trilogy,” cement Hemingway’s public persona in the popular imagination, which was Hemingway’s role as the cultural impresario on hunting, primitive cultures, and travel (again, see All Man! for more on this).

Charles H. Baker and EH, deep drinkers the both

It was also at this time that others sought out Hemingway for insight into how to “live the good life.” For example, Charles H. Baker (pictured here with Hemingway and marlin [R.I.P.]) a journalist, editor, and friend of Hemingway’s, published a few of Hemingway’s favorite drink and food recipes in his The Gentleman’s Companion exotic food and drink books, including Hemingway’s conch salad and his Death in the Gulfstream Reviver, which amounts to a hi-ball glass of crushed ice, juice of a lime complete with lime carcass a la a rickey, four healthy dashes of Angostura, and fill with Holland gin (I use Bols). Crisp, bitter, strong, or as Baker puts it: "It is reviving and refreshing; cools the blood and inspires renewed interest in food, companions and life." But this recipe doesn't convey the joie de vie of Baker's account. To my way of thinking, The Gentleman's Companion is as much of a classic as The Sun Also Rises (and, really, more entertaining). A few years before, in 1935, a collection of famous authors’ drink recipes titled So Red the Nose, or Breath in the Afternoon, lead off with Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon Cocktail, which I include here:

"Death in the Afternoon" Cocktail from So Red the Nose, 1935

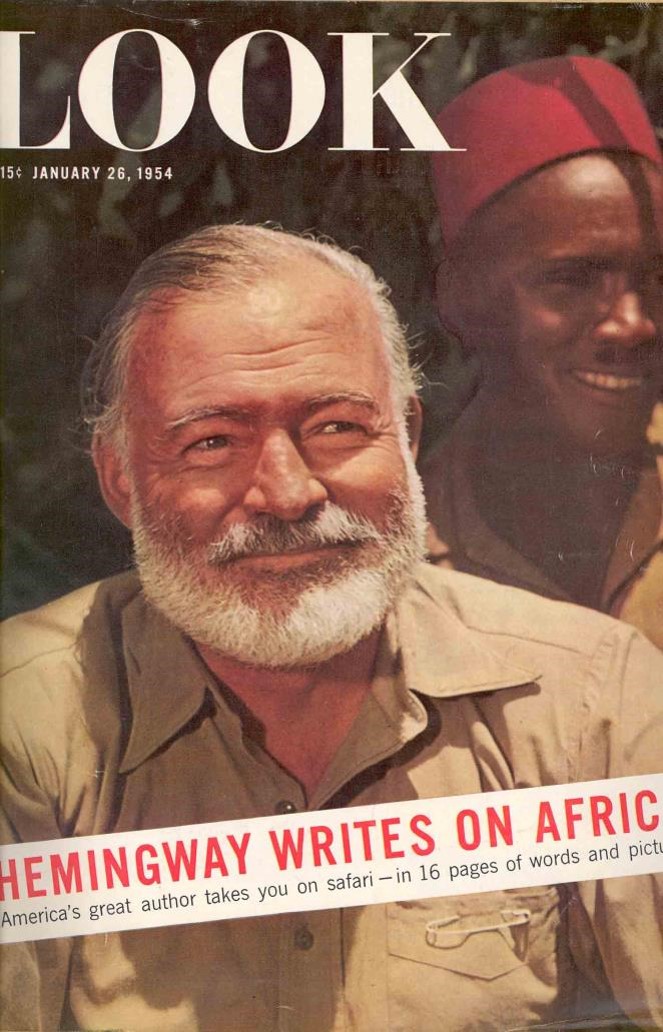

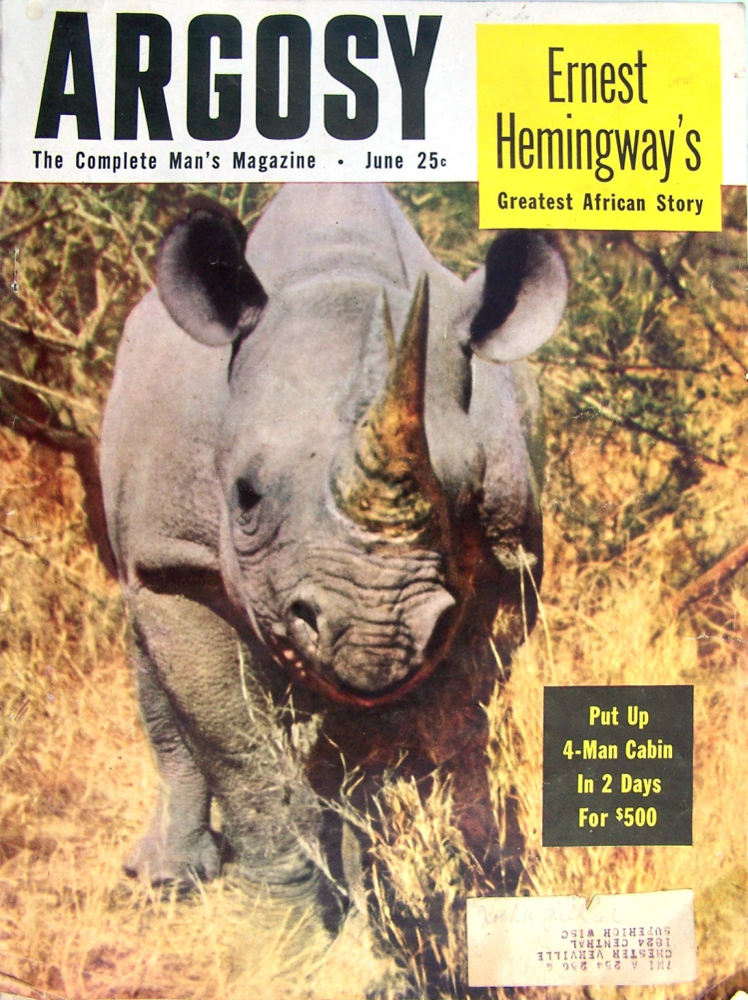

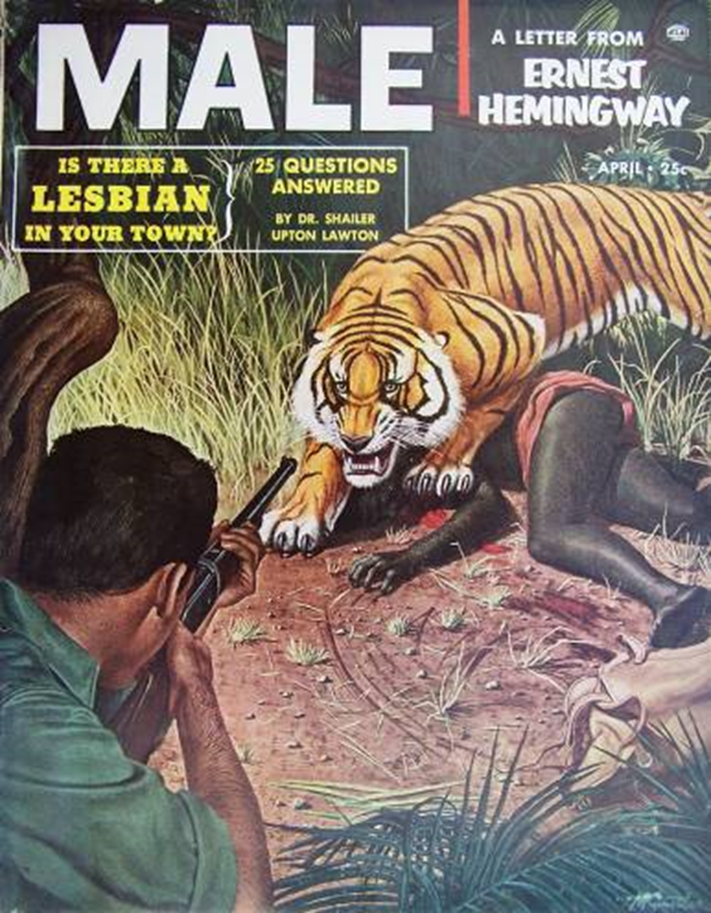

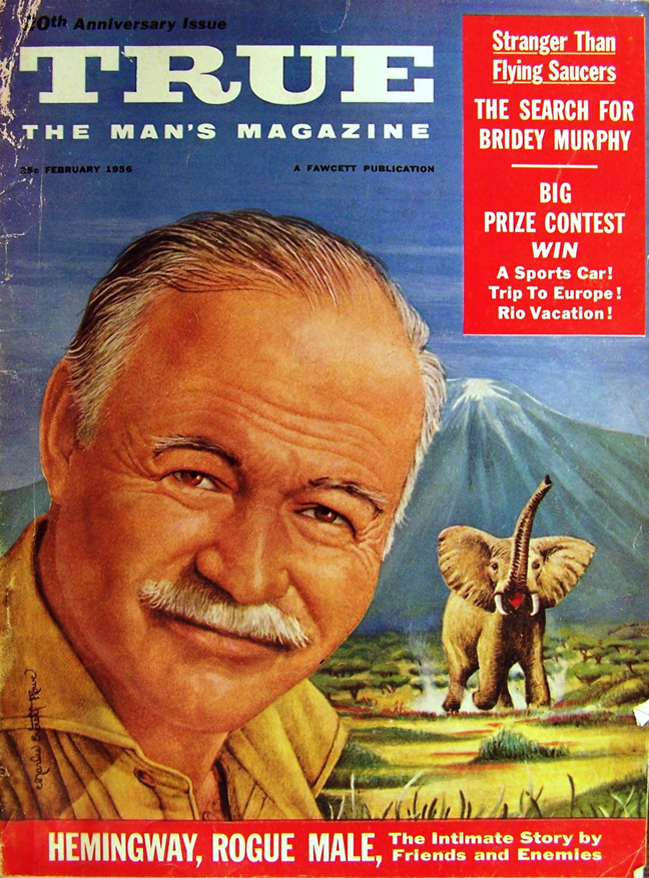

The results of Hemingway’s performance in his non-fiction, as well as his growing public exposure resulted in cartoonish pastiches, such as above or, more telling, this paper doll from Vanity Fair magazine, which shows Hemingway in all his guises – notice though that the “natural one” casts Hemingway himself as Primitive. In short, this was Hemingway’s public persona throughout the 1930s and 40s (or at least one of them. He was also the military expert, prize fighter, fisherman, etc). And as America emerged from the Second World War, his fame continued to grow. For Whom the Bell Tolls was selected for the Book of the Month Club and The Portable Hemingway was published; as were numerous popular paperback editions, including the Armed Service editions of “Selected Short Stories” (which included both “The Snows of Mt. Kilimanjaro” and “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber”). These publications guaranteed that the author reached a larger audience than ever before, paving way for his apotheosis into cultural icon during the 1950s. We can just look at the following magazine covers and articles:

- Look magazine, 1954, offers a photo account of his second trip to Africa

- Argosy, 1953, reprints sections of Green Hills of Africa

- Male Magazine, 1954, with a letter from Hemingway (and this odd headline, “Is there a Lesbian in your Town?,” which of course draws our attention to the decades own policing of the safe boundaries of gender)

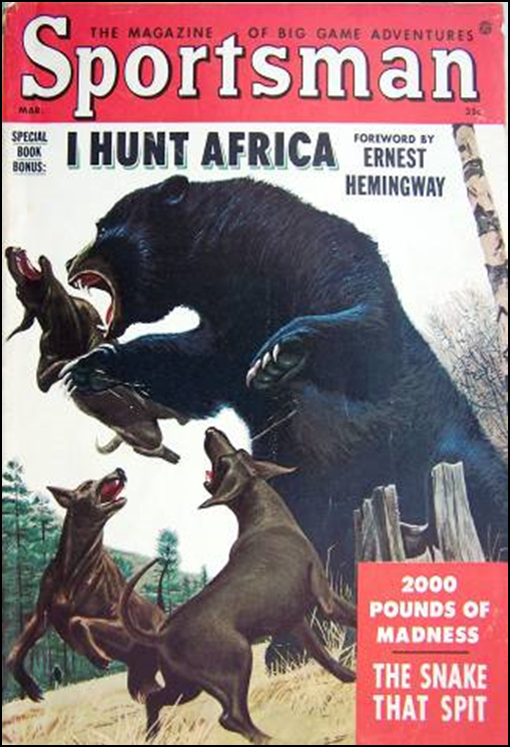

- Sportsman, from 1955 reprints Hemingway’s pretty self-serving forward from I Hunt Africa

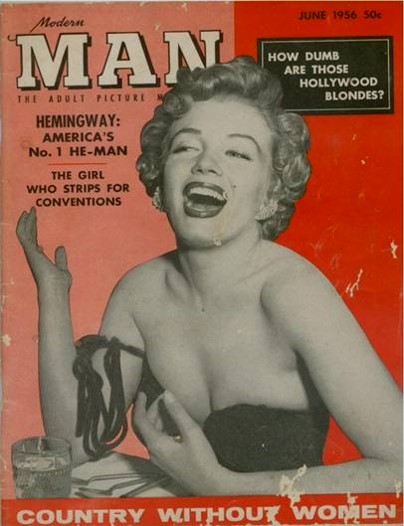

- Modern Man, 1956, proclaimed Hemingway “America’s No. 1 He-Man.”

- True Magazine from 1956, features “Hemingway: Rogue Male,” obviously equating Hemingway with the rogue elephant behind him.

It is interesting that Hemingway is so conflated with Africa when, really, his African writing, up to this point, only consisted of Green Hills, two short stories, and three Esquire essays. Given that, it is apparent there was something about Hemingway’s persona that appealed inordinately to the mindset of 1950s America. This becomes all the more evident when we look at the general fad for the safari during the decade. There were dozens of themed magazines on hunting: Peril, Safari, Man’s World, Sportsman, Male, and Real for Men. Even Uncensored featured a cover story on “Exposing Safari Sex.” Such middle and working class magazines offered vicarious adventures that reaffirmed a black and white view of the world -- life and death, without the pressures of family, job, commute, and cold-war politics. Instead, man’s struggle was redrawn as Man vs. Nature, Man vs. Animal, Man vs. Cannibal, etc. Considering 1950s culture, and America’s transition from the trauma of the Second World War, this fascination for escape to a simpler life, as represented in these magazines, isn’t surprising. The war-time tensions for millions of men were replaced by the cultural pressure to return to normality; the Man in the Gray flannel suit was expected to trade the fox hole for the pressures of Madison avenue and suburbia with stoic reserve – despite the fact that this normality was now that of the atomic age, with heightened threats of nuclear war, the red scare, horrible racial discrimination, and conservative and constricting gender roles.

Tiki Culture and the Modern Primitive

We can take this further and say that 1950s culture was defined by the need to escape a culture of containment, whether it was just to escape from the wife and kids for a weekend fishing or, for the single man, escape to the fantasy life of the bachelor pad and lifestyle so well defined by Playboy-like magazines. Or, it is a combination of all the above – a safe escape to an exotic world, primitive in its décor, simplicity, and setting – and one in which the conservative values of the mid-century middle class could be traded for a “howl and dance” to borrow a line from Heart of Darkness. This is the promise and appeal that both the Hemingway lifestyle and Tiki culture held for 1950s America.

Tiki as suburban escape from the modern

Just as the avant-garde retreated to the primitive in the face of modern industrialism – the technological slaughter of the first world war being the obvious culmination (and again, I remind you of the shell-shocked mindset of “Big Two hearted River” here), the 1950s return to the primitive was in part due to the even more extreme horrors of the second world war, culminating in the atomic bomb. For the most part, this nuclear age was captured in streamlined mid-century modern design, both artistic and industrial. As sputnik seemingly became the design motif for every roadside motel and streamlined fin-tail, there was an equally prevalent reaction against the space age in primitive motifs. And since the technological promise – or shall I say threat, was so much more prevalent, so was the appeal of the primitive. Now, rather than being solely the interest of an avant-garde subculture, modern primitive was popular culture. This illustrates how modernism of the 1920s became the culture of the 1950s.

Tiki culture, like so many other modern fads, has no clear starting point, but many different manifestations and pre-cursors. We can see the publication and ensuing documentary of Thor Heyerdhal’s Kon Tiki in 1950, as giving it its name. Heyderdal crossed the Pacific in a balsa raft in order to show that South American’s were possibly the settlers of Polynesia, and in so doing captured the popular imagination, giving birth to many Kon-Tiki hotels and bars. But before this, there was a fad for Polynesian themed restaurants, starting with Don the Beachcomber’s Hollywood bar in 1934 (originator of The Zombie and Pupu Platter) and then, almost contemporaneously, Trader Vic’s in San Francisco. Both claimed invention of the Mai Tai. Of course, the idyllic vision of Polynesia and its popularity grew during and after World War II, and was cemented with James Michener’s Tales of the South pacific in 1947, which was the basis for Rodger and Hammerstein’s South Pacific in 1949.

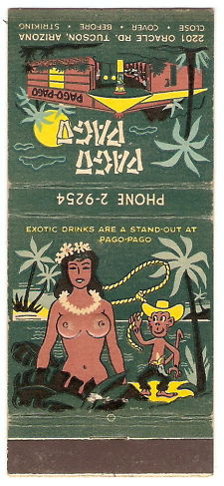

By the mid-1950s, Hawaiian themed restaurants and bars were everywhere in the United States, each featuring a wide range of now classic exotic cocktails – Mai-Tai, Zombie, The Fog Cutter, Planter’s Punch, etc., and each restaurant was designed as a phantasmagoric escape from suburban life that transported patrons to islands or jungles depending on their theme, with stage shows of fire dancers and limbo, inside rainstorms, floating island stages on inside lagoons. They had names such as Aloha Joes, The Tonga Room, The Mai-kai, Tiki Bob’s, and The Safari Room. And these restaurants weren’t only Polynesian, but could transport the diner to any exotic locale as long as it was an immersive experience and based upon a white fantasy of the foreign, hence they often mixed African, Caribbean, and middle-eastern décor. (One could even make an argument that San Francisco’s famous El Matador could count as a Tiki bar). In general, these restaurants made people into consumers of an idealized fantasy of the primitive.

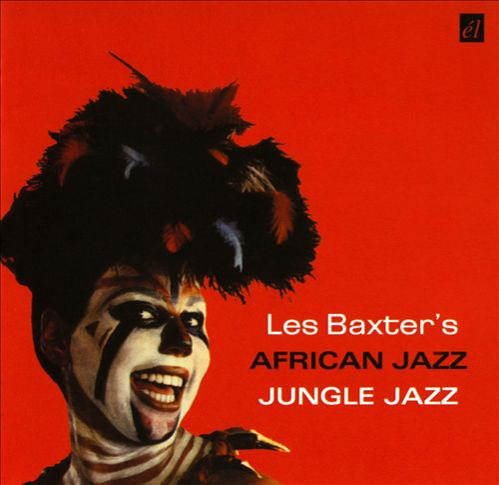

To understand how the concept for these bars worked, we can look at one of their favorite exports – Exotica music, which blended the influences, rhythms, and instruments from different cultures seamlessly into “cocktail music”: part jazz, part lounge, and, for all of its exotic inspiration, very white. It is designed to transport the listener outside of boundaries of mainstream music, but it is assuredly not the threatening chaos of free-form jazz or bop. Les Baxter’s The Ritual of the Savage, from 1951, is the perfect example. The liner notes ask: “Do the mysteries of native ritual intrigue you… does the haunting beat of savage drums fascinate you? Are you captivated by the forbidden ceremonies of primitive peoples in far off Africa or deep in the interior of the Belgian Congo?” And the covers answers the question by drawing the parallel of the modern couple getting ready to, errr, perform the “Ritual of the Savage,” perhaps while listening to the track Love Dance which, as the liner notes tells us, featured “The Beat of the tom-tom… bringing together the entire native populace for a ritual as stimulating as it is sacred. Here is the music for a slow, surging, and erotic dance… a dance as seductive and pulsating in its concept as in its execution… gentle in tempo… violent in execution.” It is the whitest music ever inspired by Africa.

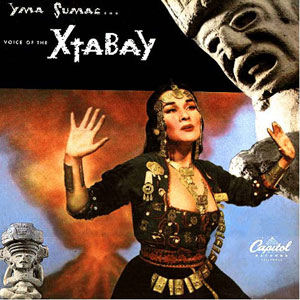

With the fad of exotica, every suburbanite with a hi-fi was able to schluff off the stultifying and conformist mantle of mid-century America and return to the primitive struggle, the primal scene of life, to go ashore “for a howl and dance” like Conrad’s Kurtz. Exotica transported listeners to The Middle East, Havana, Hawaii, and the Caribbean, making Limbo the “latest party rage.” There was even exotica from primitive cultures long disappeared, like that of Yma Sumac, a self-proclaimed Incan Goddess. But transformation wasn’t restrained to just music. Suburbanites could also transform their own houses into exotic locals through design objects such as those by Witco, the famed suppliers to Americans of all things Exotic.

There is a direct genealogy between the Primitivism of the 1920s and this popular form. Indeed, we can even see the direct and literal link across these renditions of African masks, from the original Fang mask, to the sculpture by Modigliani from 1911, to this mug from Tiki Bob’s. I am only half facetious with this genealogy: Both the subculture of the 1920s and the popular culture of the 1950s looked to the primitive as a means to escape from modernity, both constructed the ethnic other along sensualized and erotic lines, and both forced a reflective disconnect between oneself and one’s surroundings. What is the difference between French surrealists wearing African masks and the mid-century tiki-party, where everyone dressed in hula skirts, sipped Mai-Tais, and danced the limbo. Well, what is missing is the stylistic “shock of the new” – but this of course smacks of an elitist idea that art loses its potency once absorbed into popular culture. I would prefer to think of Tiki-culture as the culmination of modern primitivism’s initial trajectory, a popular modernism with all of its troubling and liberating aspects intact. And the popularity of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea illustrates this.

The Old Man and the Sea as modern primitive

Hemingway published two major works in the 1950s: Across the River and Into the Trees in 1950 and The Old Man and the Sea in 1952. Of the two of them, Across the River and into the Trees was the more blatantly or stereotypically modernist work, with a complicated narrative structure, an unstable temporal framework, a flawed and traumatized hero conquering fear, doubt, and war-time injury. It was a Hemingway that we expect – the European setting of Venice, duck-hunting, lots of drinking, even some hemingwayesque lovemaking (which, don’t worry, I won’t read). Yet this book met with critical scorn and charges that Hemingway’s reign was over, his talent gone. The Old Man and the Sea, on the other hand, was Hemingway’s greatest success, perhaps because it is much more in keeping with the modern primitive that appealed to the 1950s mindset.

The Old Man and the Sea is one of Hemingway’s most simplistic narratives, which is itself reflected or substantiated by the simplicity of the life and philosophy that it portrays. The story is taken down to its basic components, little more than a fish story or a “one that got away” tale, but Hemingway brings to it hidden depth through the addition of reoccurring visual and symbolic images, much like a cubist painting. These repetitive images are cruciform, Santiago as Christ (carrying the mast of his ship up the hill to his cottage, falling multiple times like Christ’s march to Golgatha; Santiago’s bleeding hands the stigmata); and the lions on the beach that Santiago dreams about. It is this image that we are to take away with the book’s final line “The old man was dreaming about the lions.” The images of the lions have the flatness and naiveté of a Henri Rousseau painting, and obviously stand for Santiago’s (and hopefully the reader’s) idealized dream of a purer and now lost state of nature, just as Santiago himself symbolizes a purer (and primitive) relationship between man and nature, an idealized picture much like those Gauguin painted, such as The Poor Fisherman. The complexity and destructiveness of modern life is woven throughout the novel but conspicuous in its absence: The fishing styles and motor boats of the other fishermen, the radios, coast guard, and sea planes we never see or hear, the tourists who misunderstand Santiago’s battle are all the counterpoint to the primal struggle of the novel. The simplicity of Santiago’s life is primitive in comparison to the modern world, and Hemingway lets us know this by giving us that penultimate vision of the tourists, ourselves. Therefore, the story works exactly along those same dialectic dynamics as other works of modernist primitivism.

By embedding Hemingway’s style in the larger tradition of modern primitivism, I’ve contextualized his popularity, and specifically that of The Old Man and the Sea, with the mid-century’s fascination with the same. We can see how the book appealed to the sensibilities behind America’s fascination with Tiki culture– an idealized primitivism that offered alleviation from the tensions and traumas of modern life. Hemingway himself was not immune to this cultural need to break with modern society and return to an idealized past, as True at First Light makes clear, with Hemingway’s own honorary membership as Masai and taking of a native bride, his own “howl and dance.”

One of the many EH interviews from 1950s men's magazines

In the years following The Old man and the Sea, Hemingway’s fame continued to grow, helped along in dozens of portrait pieces in popular magazines. Over the course of the decade, the public persona of the man as adventurous bon-vivant overshadowed the man himself. Interviews such as these concentrated on lifestyle – often because Hemingway refused to discuss his writing. One article, “Muy Hombre,” made much of his drinking eight Papa Doble Daquiris over the course of the interview in the Floridita bar. Others latched onto his gruff way to deal with intruders, and his larger than life flourishes. These only compounded with Hemingway’s death, when biographies read more like fiction than fact. Is there little wonder then that today, the popular image of the author is inseparable from exotica, cocktails, and the good life? Much like how Modern Primitivism constructs and ideal image of the other, whether Polynesian or African, American culture has constructed an idealized version of Hemingway himself, separate from the man until he has been co-opted and applied to our own popular needs and desires.

For more reading, see:

Suzanne Del Gizzo's "Going Home: Hemingway, Primitivism, and Identity" in Modern Fiction Studies, v.49 n.3 (Fall 2003), pp. 496-523

Sven Kirsten's wonderful Tiki Modern, NY: Taschen, 2007.

This post was originally presented as the plenary talk at the Sun Valley Hemingway Symposium in 2013.