As I start researching my Cocktail Book book – an illustrated history of the cocktail book – I keep coming up against the issue of definition: how shall I define the cocktail book, what are the cocktail book’s forerunners, must the book contain “cocktail” recipes or just mixed-drink recipes, if an early cookbook has a large proportion of drink recipes, is it a cocktail book, etc. Such definitional questions aren’t always simple to answer -- and all of them effect what we consider the earliest "drink books."

The book that is commonly accepted as the first cocktail book even raises some questions. As many people know – thanks to David Wondrich’s excellent Imbibe – the first actual cocktail book was Jerry Thomas’ 1862 How to Mix Drinks or the Bon Vivant’s Companion (NY: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1862), also known as The Bartender’s Guide depending upon the edition. Whereas drink recipes appeared in many other books, newspapers, and magazines previously, The Bon Vivant’s Companion is the most extended and focused treatment of drink mixing up to that time – though, to a certain degree, the book’s real contribution was not so much due to the recipes contained within as its substantiation of the craft by making “insider” knowledge available to the general public.

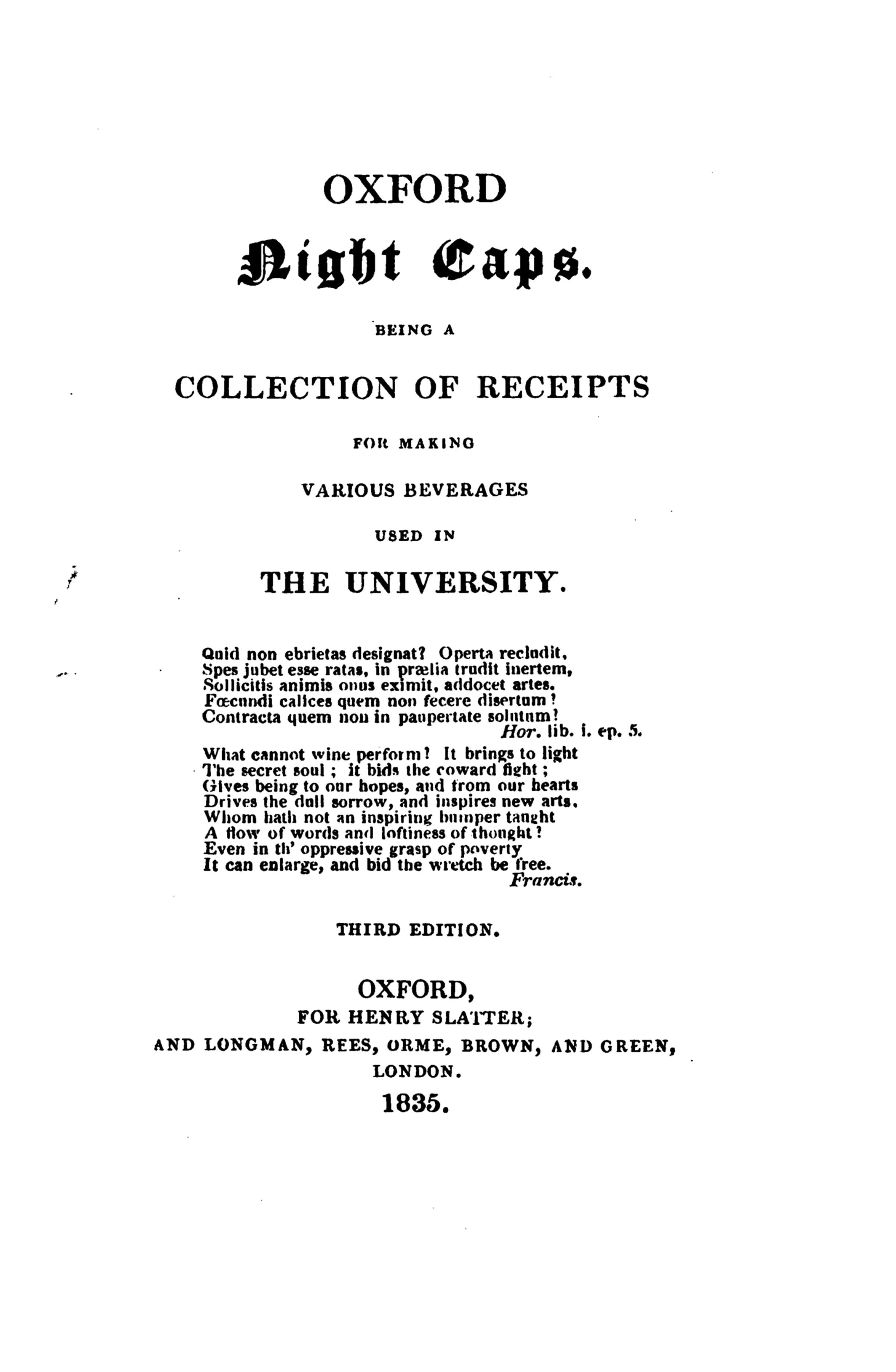

There were books with recipes for Punches, Shrubs, Smashes, etc. available long before Thomas’ book, for example: Oxford Night Caps being a Collection of Receipts for Making Various Beverages used in the University (London: Henry Slater et al., 1827) and The Publican and Spirit Dealer’s Daily Companion, or Plain and Interesting Advice to Wine Vault and Public House Keepers, on subjects of the greatest Importance to their own Welfare, and to the Health, Comfort, & Satisfaction of their Customers & Society at Large (London: Peter Boyle, 1795). These two books illustrate both the type of book available before Thomas’ volume and what sets his apart.

Oxford Night Caps went through multiple editions (1827, 1831, 1847, 1871), and could be said to be as influential in its way as Thomas’ book – most prominently in the area of punches and possets. It is most famous for a series of ecclesiastically-named drinks: the Bishop (a hot port punch spiced with lemon, cinnamon, cloves, mace, ginger, and all-spice); the Lawn Sleeves (named for the odd shaped sleeves of a Bishop’s garment; more or less a Bishop with madeira or sherry instead of port and the addition of “calves-feet jelly,”); the Cardinal (claret rather than port); and the Pope (champagne instead of port). Though the book was published anonymously, it has been ascertained that the author was one Richard Cook, a “scout” (which was the equivalent of a combination valet and housekeeper privately hired by a student; known as a "scout" at Oxford and "bedder" at Cambridge) for Oxford students. He seems to have been quite a character and famous in Oxford's culture of the day since he is fondly remembered in many of the Victorian reminiscences of Oxford.[i] Not only was he characterized as quite a famous homespun philosopher, but as a faithful -- and very erudite -- scout. In 1882, Frank Buckland, the naturalist and son of a Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, reminisced about how “an old college scout at Christ Church, Oxford, one ‘Cicero Cook,’ held an aphorism that a man’s character could be told by the books and surroundings in his study.”[ii] Cook, who was known familiarly by the nickname “Cicero,” would write undergraduates’ Rhetoric essays for a fee, and, if the literary allusions and Latin quotes in Oxford Night Caps are any indication, must have been quite learned.

Given Cook’s vocation as Oxford “scout,” I suppose that Oxford Night Caps can be considered a Butler's or Valet's guide, a genre which, along with the Publican’s Manual, are the two direct antecedents of the cocktail book -- though I think that the intended audience for Oxford Night Caps was much broader than these other genres, yet it also deviates in subject matter and style from most cookbooks which were aimed at a more general audience. Cookbooks like The London and Country Cook: Or, Accomplished Housewife (by Charles Carter, 3rd edition 1749, “revised and much improved by a Gentlewoman”) may have the sporadic recipe for something like “Orange Brandy” but for the most part avoided extended attention to spirituous liquor. Butler’s guides were unlike most general cookbooks of the latter 1700s in that they dedicated a portion of space to drink recipes, the care and service of wine cellars, and some home manufacture of alcoholic beverages. Publican’s Manuals, on the other hand, were devoted to the care and manufacture of liquors – how to store, clarify, and make batch alcohol. (The Schultz portion of Jerry Thomas' book gives a good idea of what I'm calling the Publican's manual, as does The Publican and Spirit Dealer’s Daily Companion.) Butler’s Guides and Publican’s Manuals were for narrow audiences (unlike most cook books). I will dedicate future blogs to both of these genres, but suffice to say that, even more than Thomas’ book, Oxford Night Caps deviates from its antecedents.

Given that Oxford Night Caps was published as an inexpensive 43 page pamphlet, and went through numerous editions, I daresay that the book wasn’t meant as a “trade” volume like The Publican and Spirit Dealer’s Companion, but rather as a popular text for students -- or those who would like to emulate their lifestyle (needless to say, the Oxford students' lifestyle, even when acting out, set the norms for genteel masculinity within Victorian popular culture). That the pamphlet was published anonymously supports this claim since a guide for butlers, valets, and publicans would most likely tout the authors’ credentials. If Oxford Night Caps was marketed for either Oxford students or a popular audience familiar with the students’ propensity for boozing, hence forwarding a negative stereotype of the hallowed institution, then it explains why it was written anonymously. In short, Oxford Night Caps was the first popular publication dedicated solely to mixed drinks. Of course one can argue that the upper class clientele of Oxford students isn’t popular per se, but the book was influential enough to get mention and recipes reprinted in William Hone’s popular almanac The Year Book of Daily Recreation & Information in 1832.[iii]

In Imbibe, David Wondrich gives a good description of the composite make-up of the first edition of Jerry Thomas’ book: part drink-mixing guide and part – the greater part – guide for compounding liquor (Christian Schulz’ A Manual for the Manufacture of Cordials, Liquors, Fancy Syrups, etc., etc., translated -- a “Distiller’s” or publican's manual). Dick & Fitzgerald were a publisher of popular pamphlets and trade books alike: “how to” manuals, etiquette guides, almanacs, and two other books on liquor manufacturing. The inclusion of Schulz’ manual, as well as Dick & Fitzgerald’s somewhat schizophrenic catalog of book, muddies the water in terms of knowing exactly what the intended audience was for Thomas' book, as does the book’s marketing. Initially conceived in 1859 as “The Bartender’s Guide, or Complete Encyclopedia of Fancy Drinks,” it was finally published as How to Mix Drinks or The Bon Vivant’s Companion at $1.50. Subsequent printings jumped to $2.00 and finally to $2.50, quite expensive though it is unclear when these later printings were (publishers didn’t always reset their type when reprinting). Some copies had embossed covers reading “Bartender’s Guide” and others “How to Mix Drinks.” I’d like to do a complete bibliographic comparison of covers, pricing, and dates of the book while considering the prices of other similar D&F books to see if the price jump had anything to do with war-time shortages of paper, the book’s popularity, or just inflation. Regardless, considering those prices, I think it is safe to say that the book wasn’t necessarily for a general audience (and if it was ever meant to be, just the Thomas section would have been published as a $.75 cent pamphlet, like Hillgrove’s A Complete Practical Guide to the Art of Dancing (1863) and other popular Dick & Fitzgerald publications).

The fact that Thomas’ book is the first “trade” book of mixed drinks or that it contains twelve recipes for “Cocktails and Crustas” shouldn’t distract us from the importance of contemporary butler’s guides that contain cocktail recipes (more on these later) or earlier popular books such as Oxford Night Caps.

In terms of the simple dissemination of recipes, newspapers and magazines would have had larger circulations than either Thomas’ or Cook's books and would have reached a much larger – and more general – audience. Of course, both the ephemeral aspect of such forms and the primacy of the “book” in terms of archiving makes searching for recipes difficult. But of course, magazine and newspaper appearances wouldn’t be “books,” which brings me back to my initial statement about the difficulty of definition. In future blogs I’ll look at Cocktail Books that aren’t actually “books,” such as “Dial-a-drink” wheels and cocktail “slide-rules,” but in the meantime I’m finding the process of questioning categories and definitions, such as “cocktail” and “book” an important part of the creative process as I start to “wrassle” out the dimension of the project.

[i] See, for example, “ΕΠΕΑ ΚΑΪ ΠΡΑΞΪΣ, or, Sayings and Doings in the University of Oxford,” in The Metropolitan Magazine, September 1840 (v29, n.1), and “Ruskin at Oxford” by the Very Rev. G.W. Kitcin, D.D., F.S.A., Dean of Durham, in St. George Magazine, January 1901 (v.4, n.13).

[ii] Frank Buckland, Notes and Jottings from Animal Life, G.C. Bompas, ed. (London: Smith, Elder, and Co, 1882), 229.

[iii] William Home, The Year Book, of Daily Recreation & Information: Concerning Remarkable Men, Manners, Times, Seasons, Solemnities, Merry-makings, Antiquities & Novelties, Forming a Complete History of the Year. (London: W. Tegg, 1832).